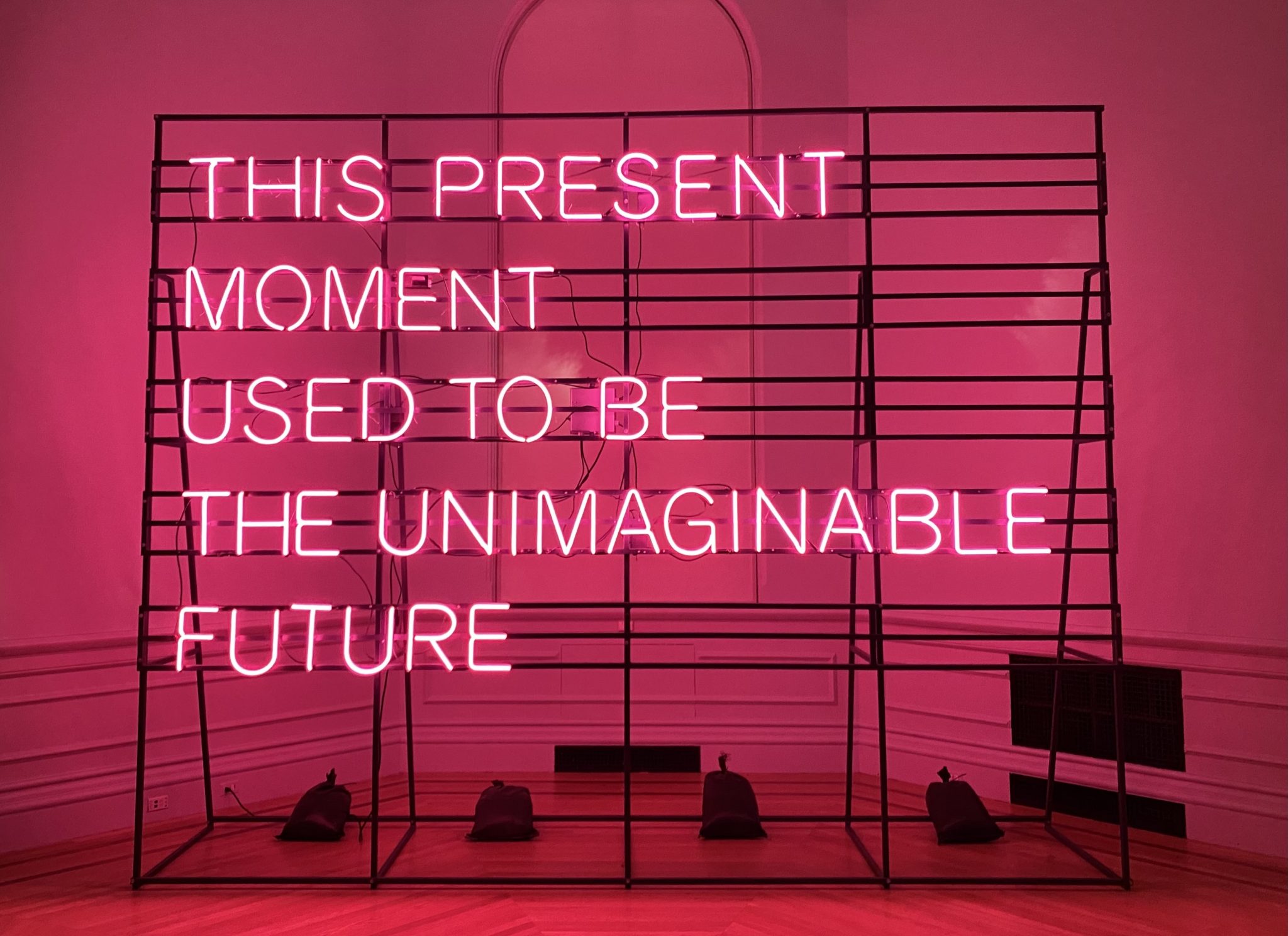

Pulling inspiration from futurist and author Stewart Brand’s ideology, a neon pink billboard illuminates to bring its viewers into the present – a moment marked by social reckonings that empower communities and demand accountability.

“THIS PRESENT MOMENT USED TO BE THE UNIMAGINABLE FUTURE,” the sign read before a portion of dull lights. “THIS MOMENT USED TO BE THE FUTURE.”

Artworks that imagine a better world to create one are at the center of the Renwick Gallery’s current exhibition, This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World, until April 2.

The American artists featured in the gallery push boundaries of representation and inclusion through the interplay of the past, present and future. The exhibit features surgical masks into embroidered artwork and quilts transformed into protest banners. Other pieces include crafts seeking to restore humanity’s relationship with the environment and build coalitions.

These campaigns by women and artists of color are a stark contrast to the bold activism occurring in museums across the world.

Two climate activists glued their hands to the frames of famous Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s paintings at the Prado museum in Madrid. Another was arrested after smearing cake on Leonardo da Vinci’s renowned “Mona Lisa” at Paris’ Louvre museum.

Activists argue the devastating effects of climate change will soon outweigh the damage to a priceless painting. Other protestors further the cause with claims of art’s impending insignificance when there is no food or water left on Earth.

But attacking those institutions is not only potentially messy, but it highlights the finesse it takes to use art as a means of activism rather than a prestigious stage for championing a cause.

[Review: Cavetown’s ‘Worm Food’ melancholy feels honest]

In one part of the exhibit, coffee lids, single-use utensils and a pink plastic toy cell phone are tied to ten steel rings among other discarded plastics. Each ring, slightly larger than the last, is pulled out from the wall it’s bolted to, giving the chain the illusion it’s dragging across the ground. The 2013 piece, titled “Drag,” shows the indefinite life plastic takes on after we discard it,

“[It serves] as a commentary on our collective habits of consumption,” the piece’s curator, Susie Ganch, said in the exhibit. “To offer the viewer a tactile experience.”

This work, unlike art vandalism, conceptualizes consumer waste to turn visualization into understanding, and likely understanding into action. Meanwhile, other pieces go beyond mere reflection, crossing over into the embodiment of issues that spark intimate understanding.

A woman in glass huaraches made with rusted metal pieces of the U.S.-Mexico border fence is adorned with a virtual reality headset, breath distiller and glass backpack holding loose water. Each fragment of artist Tanya Aguiñiga’s 2020 “Metabolizing the Border” pays homage to the struggles and perils migrants face throughout their journeys to find a better life.

The opportunities for activism continue to stretch beyond these subjects, reaching into arenas of social justice. A portrait of a Black American woman with a youthful bubble braid connected with bows reflects on the structures of racism that have persisted and reasserted themselves in American society during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[Review: ‘Her Loss’ is too much Drake and not enough 21 Savage]

With her nose and lips carved from the stars and stripes of the American Flag, artist Sharon Kerry-Harlan’s quilt addresses the multi-state attempts to suppress Black voters during the 2020 election and call out efforts to enact racist voting laws.

“Despite these dire situations, resilience remains among African Americans and their allies to realize a better future,” Kerry-Harlan wrote in the exhibit.

Stitching this experience onto the quilted fabric was intentional. It serves to empower her community and its allies, but it also employs a familiar tool to elicit common ground and empathy necessary for social change.

The weaving of these personal and collective experiences into meaningful works that address societal issues is where activism is welcomed in museums. But whether its impacts outweigh the outrage stemming from art vandalism is a moment – perhaps an unimaginable one – of the future.